|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

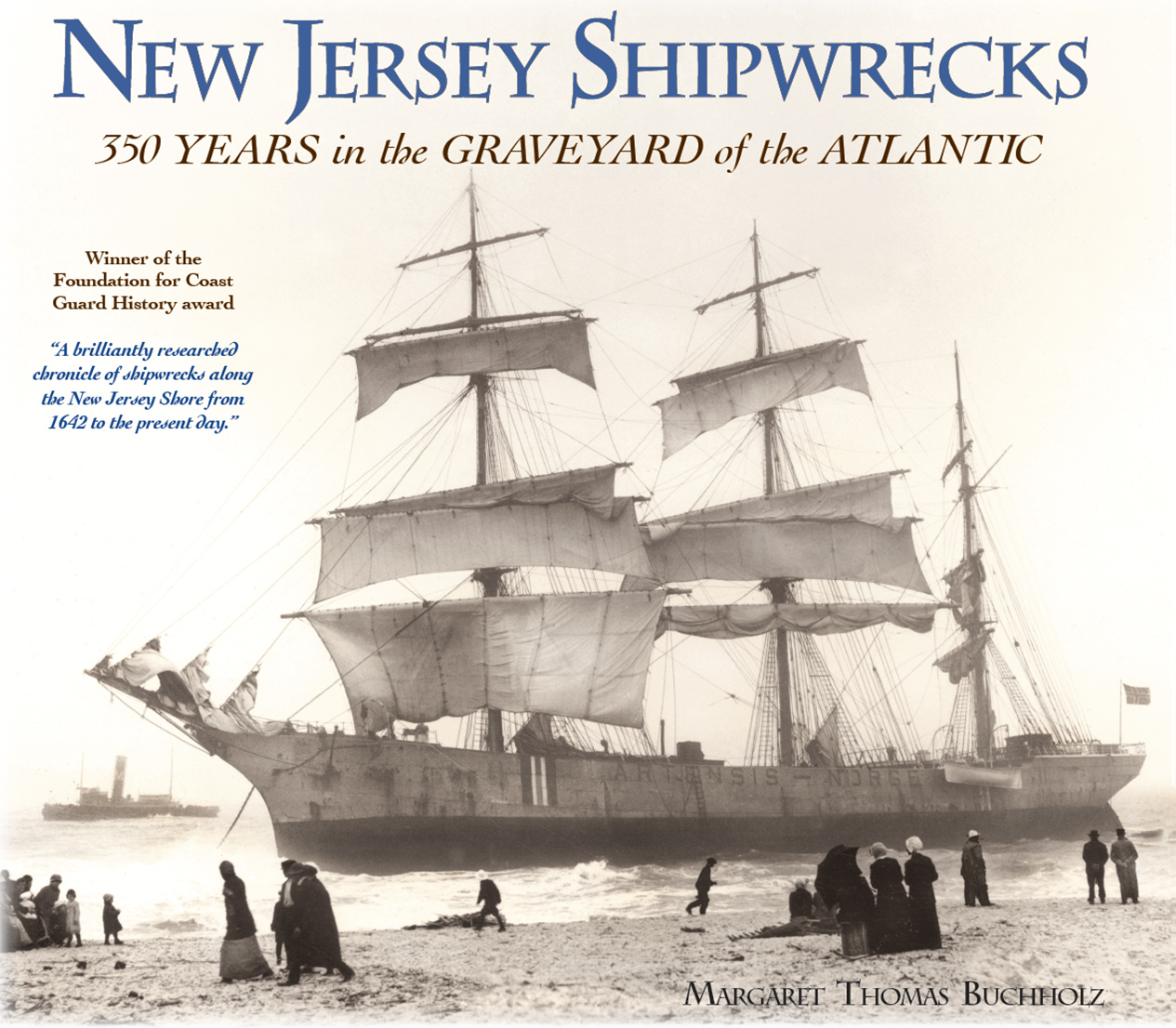

"A gripping and informative account of what appears to be America’s deadliest coastline. After reading New Jersey Shipwrecks, you’ll never look at the Jersey Shore as before. Thank God for modern engines and GPS. A great read." — W. Hodding Carter, author of A Viking Voyage and Stolen Water: Saving the Everglades from its Friends, Foes and Florida |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

$26.95 softcover ISBN 978-1-59322-050-1 |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

1890

Collision Off Barnegat Light

The beam from Barnegat Lighthouse parted the ocean’s still surface 6 miles offshore. The late October night was clear, yet dark; the moon would rise shortly. Cuban passengers in the iron-hulled, coal-fired liner Vizcaya were lingering in the saloon after their first dinner at sea. Some of the men lounged in the smoking room. Jose´ Casarego had gone to bed, tired after the New York boarding, but happy to be on the way to Havana. Chief Officer Felipo Hazas, tall, slight, and elegant looking, was talking to the second officer in his room. The 287-foot Vizcaya was heading due south at 11 knots when the officers heard the engine room bell ring full astern. They ran on deck to see what happened.

The 225-foot, four-masted schooner Cornelius Hargraves was fairly new; she had been launched in Camden, Maine, in September 1889. On October 31, 1890 she was off Barnegat under full sail on a port tack, steering northeast at about 8 knots. The ship had had a good run from Philadelphia, where it had taken on a full load of coal. First Mate Henry Perring, who before the sail had enjoyed a visit to his hometown of Fall River, Massachusetts, was on deck with Second Mate Angus Walker. At about 8:30 pm, the lookout spotted the lights of a steamer about 5 miles ahead. Perring had the right of way and held his course. Walker burned a warning torch and called Captain John Allen to come up on deck. He checked his course, eyed the steamer, and said, “I guess we can clear them.” The liner didn’t alter its course, and Perring testified at the hearing following the collision, ?It seemed as if people on the steamer were all either drunk or asleep. They did not swerve a hair’s breadth from their course, but simply rushed down upon us.? Moments after Allen made the decision to hold his course, Walker said, “We’ll strike them, Captain!” Chief Officer Hazas reached the open deck of the Vizcaya just as the two vessels collided. He later recounted, “The bow of the schooner struck us just forward of the bridge on the starboard side. The vessel’s headway had been stopped. I went to find the captain but he must have been killed on the bridge.” He tried to get to the lifeboats, but all four on the side of the collision had been splintered. He ran for the port side and had almost cut one of the boats free when the liner started to sink. “I sprang into the rigging and climbed up as the water rose,” he said. Dr. Andres Rico was in the Vizcaya’s smoking room enjoying a cigar when the impact threw him out of his chair. He rushed on deck and saw the schooner’s 40-foot bowsprit towering above them, ripping away the rigging and deckhouses. At that moment engineer Francisco Serra came up from the engine room and said that the schooner’s bow had pierced the hull and the ship was flooding. The vessel began to settle, and a woman came stumbling up to them with her little boy in her arms, screaming, “For God’s sake, save my little one!” The engineer moved to take the boy, but, Dr. Rico said, “the final tremble of the steamer came as the engineer tried to get hold of the child … he just had time to catch the fore rigging as she sank. At least twenty-five men got into the rigging, but one by one, they lost their hold.” The little boy was lost. Casarego had been thrown out of bed when the vessels collided. He pulled on some clothes and ran on deck. “Here was a pitiful sight,” he later said. “Women were kneeling, praying to the Virgin to help them, and men and sailors were running wildly about as though they had lost all presence of mind.” The liner was sinking fast, and Casarego jumped into the frigid water and climbed onto some floating spars. The Cornelius Hargraves struck the Vizcaya just behind the coal storage area. Hazas said, ?The crushing force of the schooner’s blow carried her bow clean into our engine room and the water poured in. It was evident nothing could be done to save the ship. The confusion was frightful and everyone could think only of himself. There was a terrible scramble for the rigging by some while others leaped up onto the schooner, which still lay alongside us, tangled with our rigging. The bridge where the captain had been standing was swept away completely by the long bowsprit and I think that both the captain and the third officer were killed by the first crunching blow.? Second Mate Walker said, “For the next few seconds after we struck everyone seemed to be paralyzed with fear, and there was a perfect silence. Then, as people realized the great danger, they raised agonizing cries and rushed hither and thither over the steamer’s deck. Many of them began jumping down upon the decks of the schooner, imagining that she was not as badly damaged as the steamer. Captain Allen was standing under the light of the binnacle lamp. His face was pale. He shouted to us to keep the people back and to look after the schooner’s crew first. He seized a broadax, cut away the lifeboat and jumped in and was followed by the first mate and three sailors.” Walker was forward and couldn’t get to the boat in time. He shouted to the captain to wait, since the boat could hold another dozen men. “For God’s sake, come back,” Walker said. The schooner was going down with the liner, and the rest of the crew were climbing high into the rigging. Walker took a large gangplank and jumped overboard with it. He said, “When I rose to the surface I saw men jumping into the water and soon there were thirteen Spaniards [from the Vizcaya] on it with me.” They all clung to the gangplank until a long swell tipped it over; when Walker got back on, only seven men were with him. By nine o’clock, all the others had fallen off and the stillness was absolute: “The cries and prayers of the passengers and crews were all hushed; most of the poor wretches were already dead,” Walker said. Walker started paddling the gangplank toward Barnegat Lighthouse, occasionally passing a floating body. He was bitterly cold as the wind blew through his wet clothing, but the strong 24-year-old New Englander kept moving. Paddling past a floating poultry coop, he grabbed two fat ducks and tied them to his suspenders, thinking he could eat them if he had to. But, he said, “a wave broke my suspenders and took my ducks away.” After a few more hours, he realized that no matter how hard he stroked, the current was pulling him away from shore. He was beginning to think he’d never put foot on land again. He saw several schooners and steamers, but none saw him. At about 4 o’clock in the morning, he came across Casarego on his large raft of spars; this was sturdier than his gangplank, and with his last bit of strength, he pulled himself up onto it. Both men were injured — Casarego had a broken rib, Walker a head wound — and struggling against hypothermia. When they were picked up just before dawn by the pilot boat C. H. Marshall, they were more dead than alive. When Hazas climbed into the Vizcaya’s rigging, he found himself ?a little too low, for there was quite a swell on and the water came up to my shoulders. I climbed higher. The moon rose and shone brightly on the calm, rolling surface of the ocean, and nearby, with all sails set, we saw the upper portion of the four masts of the schooner. The cold and wet were almost unbearable, and never was night so long. One of the sailors cut away a section of the foresail and wrapped it around himself and his fellows and this helped to keep the sea and intense cold off some of us.? At about 8 o’clock in the morning, the lookout on the steamer Humboldt spotted two sets of masts sticking straight out of the water. As they got closer they saw about a dozen men clinging to the foremast yard. “We hailed the approach of the Humboldt’s boats as only men who had looked on death twelve miserable hours could hail their savior,” Hazas said. Two boats were quickly lowered, and within 30 minutes all were rescued. The survivors were so cramped and stiff that they couldn’t move and had to be lifted off. One Humboldt officer said, “They were in a pitiable condition, half crazed with fear and unable to give any coherent account of the disaster. We wrapped them in blankets and dosed them with hot drinks until their teeth stopped chattering.” When the survivors could speak, they identified themselves as four officers and eight crewmen of the Vizcaya. They told how men had one by one dropped out of the rigging, unable to hold on in the numbing cold. They said all the women and children had gone down with the ship. When the Humboldt arrived in New York that morning, it was the first anyone onshore knew of the tragedy... |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Excerpt from New Jersey Shipwrecks

© 2004 Margaret Thomas Buchholz. All rights reserved. |

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||